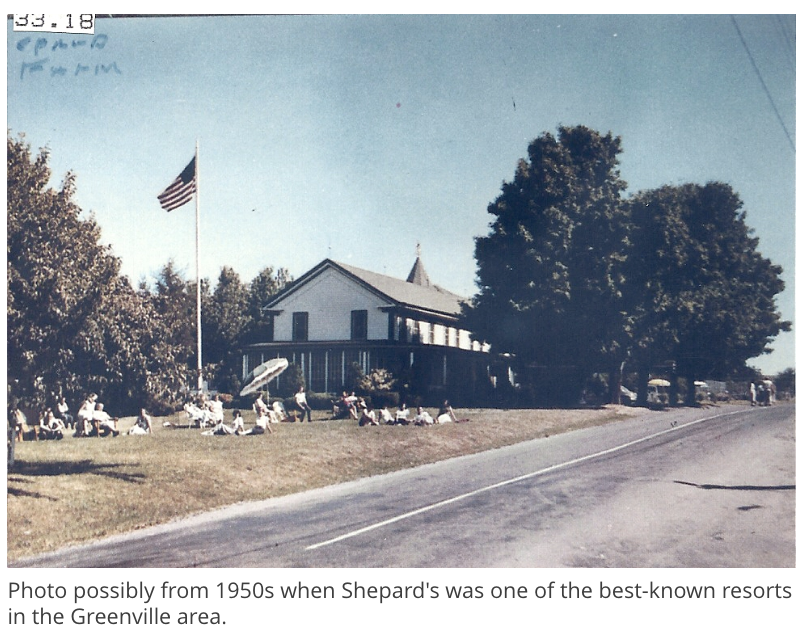

Below is a “memoir in brief” I wrote as part of a series produced by “Porcupine Soup”, a local newspaper covering the Hudson Valley of upstate NY, and the town historian of Greenville, NY, (my hometown), Don Teator. The series explores the heyday of the numerous resorts that once permeated and thrived upstate- and the decline into obscurity. It is reposted here with permission.

A few posts ago, Harriet Rasmussen’s memories of working at Balsam Shade in the mid-1940s gathered numerous reactions. The invitation for the reading public to offer their experience elicited one from Vicki Cammer (Thompson House) and now a second one.

Alicia Purdy has not only memorialized her experience but has also captured a rare look―a resort nearing its business end.

Side note: Numerous people have asked me, as town historian, when did the resort era end in Greenville? Of course, I have to answer it has not ended. Several business still function, some in the hallowed tradition of Greenville resorts, and some morphing in alternative business models. What was meant by the question often is when did the golden era of almost 30 boarding houses/resorts dotting the townscape in 1960 diminish to the three that still maintain that tradition. That answer is saved for another post.

A thank you to Alicia Purdy who captured Shepard’s (Farm) as it wound to its quiet finish and as she was employed in a position that found little demand. Wistful and nostalgic, Alicia’s account captures a feeling that the other twenty-some resorts would also experience, even if in different ways.

Alicia’s article had me reminiscing about the final few years that I worked at Spohler’s Elm Grove, lastly in 1983. Thank you, Alicia, for an alternative view.

That Summer at Shepard’s: A Memoir in Brief

By Alicia Purdy

“I’m the lifeguard.”

It didn’t matter how many times I said it, nor how many times people asked what I did at Shepard’s—no one remembered, and no one seemed to care as long as I could carry the frayed valise up to their rooms on the second floor of the main house or usher them gently toward the dining room. As long as I could sit quietly and watch Days of Our Lives each afternoon at 2 p.m. As long as I could set a nice table and remember on which side to place the forks. As long as I could properly clean a bathroom. As long as I could sit for hours and listen to guests tell me how many decades they had spent visiting Shepard’s in the summers, in the days of their youth, with groups of their single friends, with their families and now, finally, alone.

In 1994, I had spent a heady, glistening summer perched atop a gleaming white, ten-foot-tall lifeguard chair at the Ravena Park Pool proudly sporting my Baywatch style swimsuit that my mother fretted about, peering down at the football players who would stand nearby and offer me Jolly Ranchers from the snack stand and ask me to the prom.

By the summer of 1995, I had absorbed the angst of J.D. Salinger’s “Catcher in the Rye,” and I had wept over the pages of “Foxes Book of Martyrs.” I had traveled throughout South Africa and had witnessed the true ravages of racism and poverty that permeate the wider world. I had graduated from high school, and I would soon depart from Greenville, N.Y., to study Broadcasting at Geneva College in Beaver Falls, PA.

I was seventeen and had grown into a more seasoned and distinctly less dramatic version of myself, so rather than returning to the teenage melodrama of my former days, I opted to speak with Eleanor Moak after my father told me she needed a lifeguard for the pool at Shepard’s.

My parents had known the Moaks for years. My brother and I had spent evenings cordoned off in the front room—the one behind the large windows you drive by now and see from the front of the main house. It once had blue walls. It was once immaculate and pristinely decorated with antiques and chairs that made you scared to spill something.

In the blue room was an old television on which we would flip through the channels as our parents socialized with the Moaks over coffee late into the night. Eleanor Moak was much admired at my house for having remained trim over the decades by marching two miles around her dining room table each day, as my mother often noted.

By the time I was the lifeguard at Shepard’s, none of the guests really needed a lifeguard anymore. Most of them were too nervous to cross Route 32 to get safely to the outdoor pool. Most of them didn’t swim anymore. For a little while, I busied myself during my work hours skimming the odd leaf from the pool or checking the filters and rearranging the lounge chairs. Sometimes I read a book or got into the pool and swam a few laps.

Behind me were the dramatic days of jumping into the pool to help an overwhelmed kid get safely out of the water. I didn’t need my whistle to remind everyone to walk on the pavement around the pool area. I didn’t have to admonish any young girls to wear an actual bathing suit in the water. No more football players roughhousing or flirting at the desk or using the squeegee mop on the floors in the pool house. There was a perpetually serene calm at Shepard’s that I loved and hated with a contented resignation.

In the main house of Shepard’s, toward the back of the building, there was an indoor pool that needed even less maintenance, but even so, I’d dutifully check the filters and vacuum the rubbery, grass-like turf. I’d rearrange the chairs and dust the tabletops, but no one came in.

Raised by parents who had built a wonderful life with their own two hands, the work ethic they’d instilled in me caused frequent pangs of guilt for being paid to do nothing, so finally one day, I asked Eleanor if there were something else I should be doing to earn my keep. I confessed I’d been reading books by the pool and catching as much sun as my pale, freckled skin would allow. I confessed to her there were no swimmers, not for weeks.

She already knew.

Eleanor asked me to get a water aerobics class going at the indoor pool and during that week two ladies joined. They came twice during their stay with their swim caps firmly in place and together we marched and swung our arms against the resistance of the warm water. We did buoyant, gentle jumping jacks in water up to our waist and did pushups against the side. When class was over, we sat around the pool and watched Days of Our Lives together.

It was the most excitement I saw all summer.

On the tables around the indoor pool sat stacks of faded brochures heralding days long gone by with grainy images of grinning young people who looked like my grandmother when she was in her 30s, when “bathing costume” was a better word for what to wear when swimming.

Women lounging with effortless glamor and the iconic bright, red lipstick, their short, curled hair set just so. Wry men in small shorts holding tumblers of gin and tonic. The glossy images advertised the Shepard’s pools as vibrant and buzzing with young energy in the very same indoor pool area that now sat frozen in time around 1955 with the worn, faded turf and the heavy, dusty brocade curtains.

As the summer wore on, I’d walk across the street to check on the outdoor pool at intervals throughout the day, but, really, the people who visited Shepard’s no longer needed a lifeguard, nor a pool. They now needed assistance opening the windows, and someone to talk to.

“I’m the lifeguard.”

I still said it when people asked what I did at Shepard’s, but by the end of the summer, I had all but abandoned my post for hours spent unloading bags from the Lincolns that pulled up out front. It was a summer of impish winks and two-dollar tips slipping discreetly into my hand. I navigated guests down the hallways to the rooms with the pink, heavily flowered wallpaper and the knotted, white bedspreads that covered each of the two twin beds.

Sometimes the women held onto my young, strong arms as they stepped carefully onto the staircase. Sometimes the men tried to heave the bags up the stairs on their own before allowing me to hoist one in each hand and follow behind them to make sure they didn’t fall. Sometimes a guest would forget where they were going, or where they were or who they were. But they were polite with the kind of manners that you only see in the movies anymore.

Many of the guests had spent their lives visiting Shepard’s every summer and I often stood by the trunk of their sedan or lit their cigarette in the hallway or leaned against the doorway of their room and listened to what Shepard’s had once looked like, had once smelled like, had once felt like—and it was why they kept coming back. They’d raised their kids at Shepard’s, the same kids who were now traveling in Europe or living in New York City or just too busy to come anymore.

With that, the population of Shepard’s dwindled both as much from the inevitable movement of time as from the inevitable progress of age and mobility and health. In the end, its buildings also followed suit, declining gently back toward the earth until they could no longer stand on their own or be safe left alone, needing assistance, strong arms, and someone younger to be part of keeping things alive.

For me, Shepard’s had always been the sign that my journey was over—or maybe just beginning at the edge of my hometown of Greenville. “The light at Shepard’s” was a waypoint on the road, a part of the directions you gave, the only other traffic light within 15 miles, or the flashing beacon that told you to slow down, there were guests at Shepard’s.

Throughout the 20th century, Shepard’s was more than familiar or easy or affordable or tradition. For the guests who came to Shepard’s in the sweltering, muggy summer heat of 1995, the year that I was the lifeguard, Shepard’s was home.